Art In My Back Yard

Two monstrous sculptures have been on my mind lately. The first is the giant pair of sunglasses installed in Cape Town by South African artist Michael Elion; the other an eight-story-tall, as yet unrealized, Mother Canada figure envisioned for a rocky outcrop near my family home in northern Cape Breton, by Canadian non-artist Tony Patrick Trigiani.

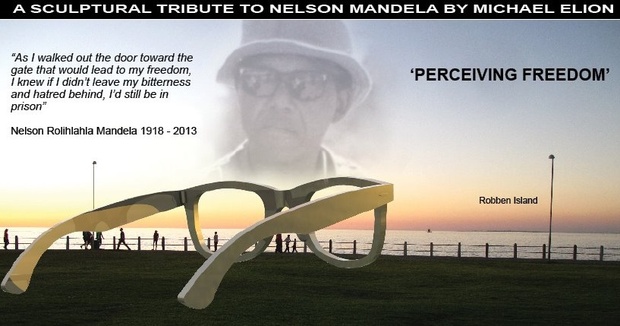

Elion’s shades are laser-cut, stainless steel Ray-Bans (not the Top Gun kind, but the Blues Brothers’). They are 20 feet across, with refracting lenses, highlighting, with rainbows, their view across the water of Robben Island. The installation is billed as a tribute to Nelson Mandela.

Elion’s shades are laser-cut, stainless steel Ray-Bans (not the Top Gun kind, but the Blues Brothers’). They are 20 feet across, with refracting lenses, highlighting, with rainbows, their view across the water of Robben Island. The installation is billed as a tribute to Nelson Mandela.

It has inspired a flurry of indignant art criticism online and in the popular press in South Africa, and for good reason. It is not clear who exactly knew what and at what stage, but it sounds to me like Elion was hustling up a storm. I can’t tell if he had the sunglasses idea first and tacked on the Mandela connection to get more attention for the project as well as some needed money from Ray-Ban, or whether the Mandela connection was there from the start but, in whichever case, he seems to have withheld the political nature of the work from the City in order to get the needed approvals.

And why? Was he trying to artfully juxtapose an almost clownishly superficial consumer icon with the over-weighted earnestness of Madiba’s legacy, perhaps offering some kind of cultural critique of wealth, status, and morality in the new South Africa? Or is it simply a boldfaced, narcissistic grab for attention? I do like the playfulness of oversized sunglasses, but clearly this public offering speaks to the vast gap between that city’s art rich and its disenfranchised poor, a cynical attempt, I think, to co-opt public sentiment to further private artistic and commercial ambitions.

Which brings us to Tony Trigiani, the man who stood on the cliff in one of the most beautiful coves in this world and felt inspired to bulldoze it to build an eight-story-tall allegory of Canada’s bereavement for long-dead fallen soldiers. He’s raising $25 million to make it happen and has already garnered massive support across Canada. But not everyone is behind him. As respected sculptor John Greer pointed out a few days ago on CBC radio, the idea of spending $25 million on a monumental sculpture project with no actual artist involved – the only plan being to “modify the gesture” of a much smaller figure from the existing monument at Vimy Ridge in France – is both artistically offensive and ill-conceived.

Which brings us to Tony Trigiani, the man who stood on the cliff in one of the most beautiful coves in this world and felt inspired to bulldoze it to build an eight-story-tall allegory of Canada’s bereavement for long-dead fallen soldiers. He’s raising $25 million to make it happen and has already garnered massive support across Canada. But not everyone is behind him. As respected sculptor John Greer pointed out a few days ago on CBC radio, the idea of spending $25 million on a monumental sculpture project with no actual artist involved – the only plan being to “modify the gesture” of a much smaller figure from the existing monument at Vimy Ridge in France – is both artistically offensive and ill-conceived.

Monumental art is made by monumental sculptors. The Vimy Ridge War Memorial was built, in the 1920s and 30s, in the wake of the First World War, by Canadian sculptor Walter Seymour Allward after his design was chosen in Canada by a federally appointed jury from 160 submissions. They first made a shortlist of 17 and commissioned a miniature model of each before they finally selected Allward’s. The Mother Canada figure is a detail in his much larger creation, a solemn, bereft figure, her back to the two imposing pillars that dominate the memorial. The work remains a national treasure almost a century later.

In contrast, during his interview on the CBC, John Greer expressed his contempt for the artistic merit of the current proposal, dismissing the notion that one could simply “modify the gesture” of Allward’s Mother Canada figure, likening it to the idea of turning Michaelangelo’s David into a dancing clown. He said that while the older sculpture at Vimy Ridge expresses the deeply felt sentiment of our nation’s loss, Trigiani’s vision is rooted merely in sentimentality.

To say that the proposed War Memorial in Cape Breton lacks an artist overlooks the immense agency, here, of businessman, Tony Trigiani. Driven by an outsized passion that would serve any aspiring sculptor well, he is now poised to build a piece of art that many have compared to the iconic Christ the Redeemer statue, towering above my current home city of Rio de Janeiro, the collaborative work of the Brazilian engineer Heitor da Silva Costa and the French monumental sculptor Paul Landowski, also, incidentally, completed in the early 1930s.

I am fascinated with the gumption that clearly must drive these monumental artists, people, by definition, inclined to invest their ideas with indelible importance.

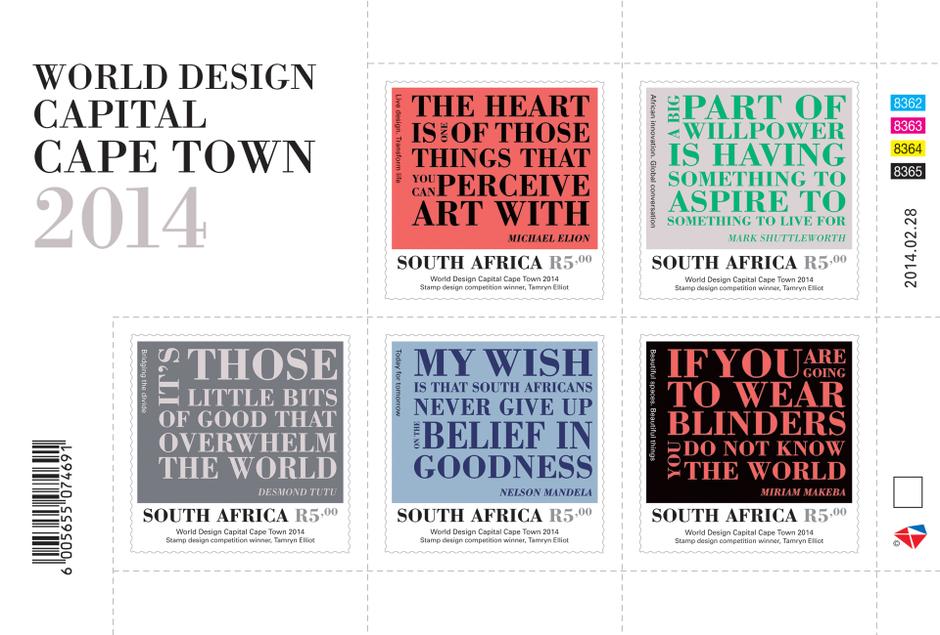

Take, for example, Michael Elion’s postage stamp project from earlier this year. The official South African Post Office published, as part of a five-stamp collection, quotations from prominent South Africans: Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, Miriam Makeba, Mark Shuttleworth, and, you guessed it, Michael Elion.

Take, for example, Michael Elion’s postage stamp project from earlier this year. The official South African Post Office published, as part of a five-stamp collection, quotations from prominent South Africans: Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, Miriam Makeba, Mark Shuttleworth, and, you guessed it, Michael Elion.

Elion’s posted wisdom: “The heart is one of those things you can perceive art with.”

I don’t in any way dispute this possibility of an emotional engagement with art. But I offer that the brain can also serve as an organ of perception. My feeling, back in Cape Breton, is that we’d do better to find an actual, living artist to envision a memorial to our fallen soldiers, hopefully one that doesn’t diminish their story by attempting to honour those great and distant sacrifices by destroying the natural beauty of the homeland those soldiers died protecting.